Understanding Philippine History through Maps and Visual Arts

Historian and Humanities Professor Ambeth R. Ocampo was the featured speaker at the September 7 presentation “Rizal, Maps, and the Emergence of the Filipino Nation,” jointly organized by the US-Philippines Society and Sentro Rizal Philippine Embassy Washington DC, in support of the Philippine initiative, the Maritime and Archipelagic Nation Awareness Month. Historian and Professor of International Studies Dr. Frank Jenista also shared his personal experience as a child raised in the Philippines, along with his professional academic and government background, with insights into the inner conflicts of Americans living in the Philippines during the turn of the century amid debates over American expansionism.

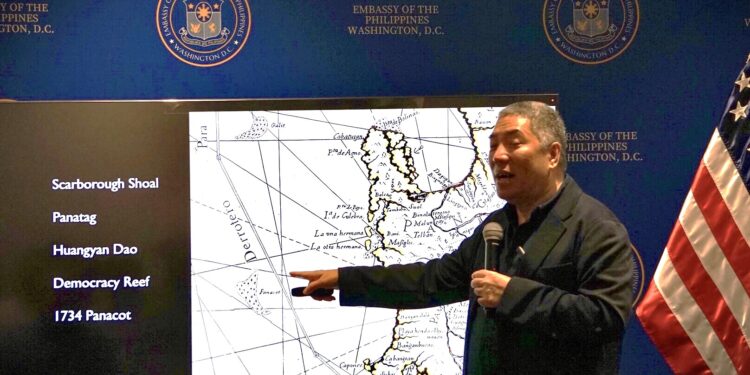

Utilizing several map images and extensive research in libraries across Europe, Professor Ocampo traced the evolution of various Philippine maps along with the development of geography from early drawings during the Age of Exploration, 15th to 17th centuries. These maps depicted the discovery of the Philippines by Magellan in 1521 and various sailing vessels to the Philippines under Spanish rule, the first reference to the name “Filipinas” after Philip II of Spain in the Villalobos map of 1543, the symbolic aspect of the Spanish world in 1761, the 1750 “Carte Des Nouvelles Philippines”, and the important scientific map of the Philippines, “Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas Dedicada” (A Hydrographic and Cartographic Map of the Philippine Islands), drawn by Jesuit Father Pedro Murillo Velarde and published in Manila in 1734.

At the turn of the 20th century, Philippine national hero Dr. Jose Rizal installed on the front lot facing St. James Church in Zamboanga del Norte, a relief map of grassy mounds shaped into the island of Mindanao where he spent four years in exile, 1892-1896. Today, tourists and locals continue to appreciate this lesser-known landmark and legacy of Rizal. Professor Ocampo also showed an image of a beautifully engraved sterling silver map encrusted in emeralds that was gifted to the widow of Spain’s Prime Minister Antonio Cánovas del Castillo. The Prime Minister was assassinated in 1897, a year after the execution of Jose Rizal.

Professor Ocampo described how history taught through maps gained importance in the emerging national identity of Filipinos. He asserted that the Philippine islands are not separated by water; rather that “the Philippines is connected by water.” Filipinos constructed bangkas, boats, ships and other methods of transportation to connect these islands.

The Murillo Velarde of 1734 shows the realities of the times. Surrounding the geographical map are pictorial engravings of the various ethnic groups living in the Philippines – Chinese, Japanese, Indian, Portuguese, and various locals carrying on with domestic life, surrounded by animals, fruit-bearing trees, maps of Manila and Guam. Inscribed on the bottom of the map are descriptions of “the natives who were well built, brown in color, capable writers, painters, sculptors, engravers, silversmiths, embroiderers, sailors, etc.(translated)” At the center is a geographical map of the Philippines that shows various islands including “Panacot” (current names, Panatag and Scarborough Shoal) and “Los Bajos de Paragua” (presently, Kalayaan and Spratly Islands). The Murillo Velarde map was a key component in the paper “Spain in the Philippines” (16th to 19th Centuries) written by Antonio Remiro Brotons and submitted as one of the testimonials in the Philippine case before the Hague Tribunal Court against China’s claims in the West Philippine Sea. In his written testimony, Brotons noted that the Murillo Velarde map was printed by the order of the King of Spain and the first exact map of the Philippine archipelago. It was used extensively by European cartographers and navigators.

Professor Ocampo recalled how the late Filipino statesman and first Asian President of the United Nations Carlos P. Romulo had insisted on including the Philippines, no matter how tiny as a dot, in the world map found in the United Nations seal. Professor Ocampo engages his students to conscientiously explore maps including updates in Google as an exercise of affirming national identity.

Following Professor Ocampo’s presentation, Dr. Frank Jenista offered his views of the early American presence in the Philippines from the turn of the century, specifically 1898, a pivotal year for America and Spanish colonies, and that remains underreported in U.S. history. At the conclusion of the Spanish-American War, the Treaty of Paris of 1898 was signed and effectively transferred the former colonies of Spain to the United States.

In Dr. Jenista’s view, Filipinos wanted independence since the beginning of the American presence, as evidenced by the resistance during the Philippine-American War (1899-1902). The strong anti-imperialism sentiment by Americans living in the Philippines and in the U.S. mainland, fundamentally changed the nature of colonialism in the Philippines in contrast to European and Japanese colonial systems. “Imperialism with a guilty conscience” and “benevolent assimilation” were terms that described the McKinley administration’s policy toward the Philippines. With local elections in 1904 and the 1907 elections of the lower house of the Philippine legislature, Filipinos gained influence over Philippine governance.

“Eighteen years after Commodore Dewey sailed into Manila Bay, Filipinos are back in charge of almost all domestic affairs in the Philippines. In 1934, the Tydings-McDuffie Act commits to Philippine independence in 10 years, and Manuel Quezon was elected as the first President of the Philippine Commonwealth,” stated Dr. Jenista.

From his personal experience growing up in his formative childhood years in the Philippines, Dr. Jenista noted an underlying closeness between Filipinos and Americans despite the geographical distance and different cultures.

Dr. Jenista observed, “I’m convinced that there is something in the nature of Filipinos and Americans that tends to make us get along well together.” He made note of the important role played by family connections, business engagements, the U.S. and Philippine government relations, and civil society as foundations of a special bond between our peoples.

Philippine Embassy Chargé d’Affaires Jaime Ascalon provided the welcome remarks, introductions, and cited the Philippine National Commission for Culture and the Arts for its support. Mark Lim of the Sentro Rizal Washington DC served as moderator of the program. In closing remarks, US-Philippines Society Executive Director Hank Hendrickson invited the audience representing academe, the diplomatic corps, members of the US-Philippines Society and local community, to visit an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery entitled, “1898: U.S. Imperial Visions and Revisions,” which displays outstanding portraits of Philippine Revolutionary leaders Jose Rizal, Emilio Aguinaldo, Felipe Agoncillo, and Apolinario Mabini.

Photo: l-r Chargé d’Affaires Jaime Ascalon, Dr. Frank Jenista, Professor Ambeth Ocampo and USPHS Executive Director Hank Hendrickson, Washington DC, 7 September 2023.